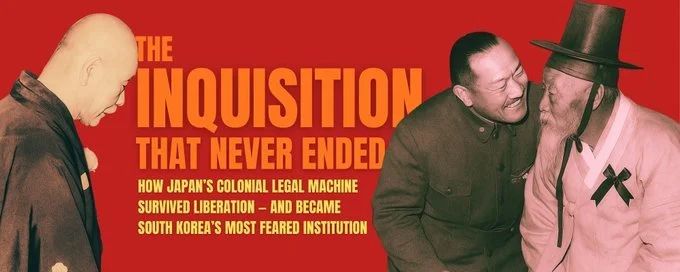

The Inquisition That Never Ended

How Japan’s colonial legal machine survived liberation — and became South Korea’s most feared institution

(Part 2 of “Three Prosecutors. Four Months. No Truth.” — Read Part 1: https://x.com/DemianDunkley/status/1986049408773886217)

Preface: The Korean Presidential Curse

Why is it, that every president of South Korea has faced ruin after leaving office—exile, prison, impeachment, even suicide? The outcomes differ, but the verdict is always the same: guilt.

From Syngman Rhee’s flight into Hawaiian exile to Roh Moo-hyun’s death under investigation, from Park Geun-hye’s imprisonment to Moon Jae-in’s looming inquiries, no Korean leader has escaped the ritual.

“In most democracies, power ends with retirement. In Korea, it ends with penance.”

Former President Yoon Suk Yeol attends the first hearing of his trial on charges including aggravated obstruction of official duties and abuse of power at the Seoul Central District Court in Seocho District, southern Seoul on Sept. 26. [JOINT PRESS COPRS] - From Korea JoongAng Daily

This is more than politics. It is the symptom of something older and deeper—a prosecutorial state engineered by Japan to control its colony, rooted in Confucian notions of hierarchy and moral order.

After liberation, only the flag above the courthouse changed. The empire’s machinery stayed intact—the same hierarchy, the same men, the same mission: control through law.

Prologue: The Inquisition Returns (2025)

July 18, 2025. Dawn had barely broken over Gapyeong when a battering ram of thirty police transport buses, under the direct command of Special Prosecutor Min Joong-ki, descended on the quiet sacred grounds of HJ Cheonwon Village—the spiritual home of the Family Federation for World Peace. The air still carried the faint echo of last night’s prayer vigil when 1,000 officers in tactical vests and riot gear swarmed the compound with military precision. Elders in slippers shuffled out of prayer halls; young believers gathered outside with their faces to the sky and hands clasped in hope.

“This wasn’t a raid. This was the empire’s ghost kicking in the garden door, demanding confession before the sun broke through the morning mist.”

What unfolded that morning ripped open a prosecutorial system forged in Joseon’s Confucian courts—torture for confessions, no defense, yangban leniency—and hardened under Japanese colonial rule, where prosecutors became imperial enforcers with Prussian bureaucracy. Japan didn’t reform Joseon’s moral hierarchy; they weaponized it for containment. And as far as the so-called liberation of 1945? We kept the chains, just swapped the masters.

July 18, 2025. Police transport buses line the streets of HJ Cheonwon Village, Gapyeong

To understand how such a scene could unfold in a modern democracy, we have to go back centuries—to the roots of Korea’s moral and legal order.

I. Before the Empire: Korea’s Confucian Justice System

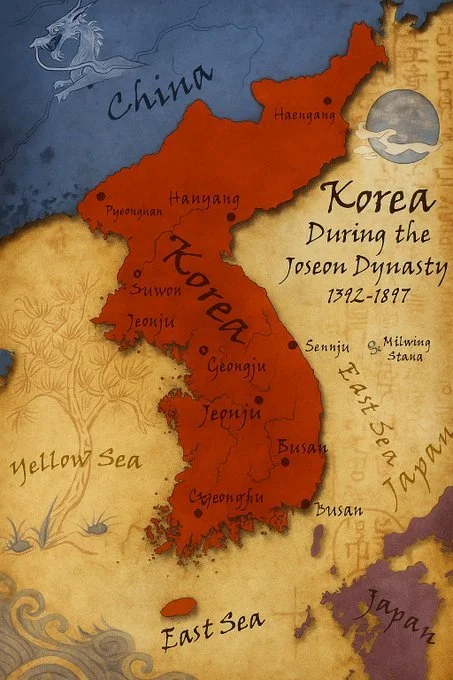

Before Japan annexed Korea in 1910, the Korean Peninsula operated under a legal and political framework grounded in Confucian philosophy, especially during the long rule of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897). The justice system of this period emphasized moral order over individual rights, correction over confrontation, and hierarchy over equality.

Law was administered by scholar-officials steeped in Confucian doctrine. The Ministry of Punishment handled major cases in the capital, while local magistrates adjudicated disputes in the provinces. The Gyeongguk Daejeon, a 15th-century state code, defined crimes and punishments. But justice remained personal and discretionary.

The strengths of this model were cultural coherence and social predictability. It reinforced a shared understanding of duty and virtue across all layers of society. The system prized harmony and restitution, often resolving disputes informally within local hierarchies.

Map of Korea during the Jeosun Dynasty

But the limitations were clear. The law did not treat all subjects equally: noble families (yangban) enjoyed exemptions or leniency, while commoners, women, and slaves faced harsher penalties. There was no concept of legal representation, no independent judiciary, and little recourse against wrongful conviction. Torture, including flogging and forced confessions, was an accepted investigative method. The emphasis on confession as proof often led to abuse.

Even in that age, Korea was not unique. Across much of the world—including Europe—justice was still harsh, public, and class-bound. Confession under duress was widely accepted as proof of guilt. The difference is that most nations transformed those systems as they modernized. Korea never truly did. It carried that moral hierarchy forward—through empire, liberation, and even democracy.

“This was not a golden age of justice, but a very different conception of what justice meant.”

Whereas modern systems seek to balance power through institutional safeguards, Joseon Korea’s justice system relied on virtue and authority as mutually reinforcing pillars. When Japan arrived with its colonial legal code, it replaced—not modernized—this inherited tradition.

II. Origins in Empire: From Berlin to Tokyo to Seoul

Korea's modern prosecution system was not born in Seoul. It was imported from Meiji-era Japan, which itself modeled its legal system on 19th-century German law. In Prussia, prosecutors were agents of state control: elite bureaucrats charged with preserving public order, not defending individual rights. Japan adapted this model to serve its own imperial ambitions.

Japanese policeman taunting Korean national.

When Japan annexed Korea in 1910, it extended its centralized, hierarchical prosecution apparatus to the colony. Korean prosecutors became enforcers of the Japanese Governor-General's authority, empowered to direct police, initiate investigations, and control trials. Their mission was not impartial justice, it was obedience to empire.

“This system was never designed to protect Korean citizens. It was built to contain them.”

This system was never designed to protect Korean citizens. It was built to contain them. Along with institutional structure, methods of interrogation and punishment were imported. Prosecutors and police relied heavily on confessions extracted through coercion. Techniques included prolonged sleep deprivation, beatings, and forms of torture like waterboarding and electric shock—methods that, disturbingly, persisted in Korea into the 1980s.

“How many Koreans today realize that their highest and most powerful system of justice was designed by Japan?”

Japanese police riding through a Korean village.

The very institution that now defines legality in the Republic of Korea was built under colonial rule, not for liberty, but for control. Its bureaucratic hierarchy, its investigative dominance over the police, even its obsession with confession; all of these were features, not flaws, of an imperial design that Korea never fully dismantled.

III. Liberation Without Reform: The Post-1945 Continuity

When Korea was liberated in 1945, many expected a full legal rebirth. But rather than dismantle the colonial system, American occupation authorities and the new Korean government retained most of its framework. The 1949 Public Prosecutor's Office Act codified the same hierarchy, structure, and investigatory powers.

America’s priority at the time was containing communism, not rebuilding Korea’s institutions of justice. The U.S. military government accepted what was already in place, allowing former Japanese-imposed systems to carry over into the new Republic of Korea. Prosecutors trained under colonial authority now served the anti-communist state.

Notably, many of the individuals who had worked within the Japanese colonial legal system—including prosecutors trained under imperial rule—remained in their positions or were rehired to lead the new Prosecution Service.

“The institutional memory, personnel, and procedures of the colonial system were not purged; they were repurposed.”

Thus, the colonial prosecution model survived into the Republic, but now serving new masters. From Syngman Rhee to Park Chung-hee, Korean presidents used the prosecutors as political tools, crushing dissent and protecting allies.

By the 1980s, critics began calling South Korea a "Republic of Prosecutors,” a state within a state, unaccountable to voters, unchecked by courts, and feared by politicians of all stripes.

Meanwhile, the legacy of violence remained. It was not until the late 1980s that credible reform efforts began to confront the routine use of physical abuse in interrogations. Victims of political repression, labor activists, and dissidents were often subjected to forced confessions through techniques inherited from Japanese colonial police. Electro-shock devices, waterboarding, and sleep deprivation were not historical rumors—they were recorded realities.

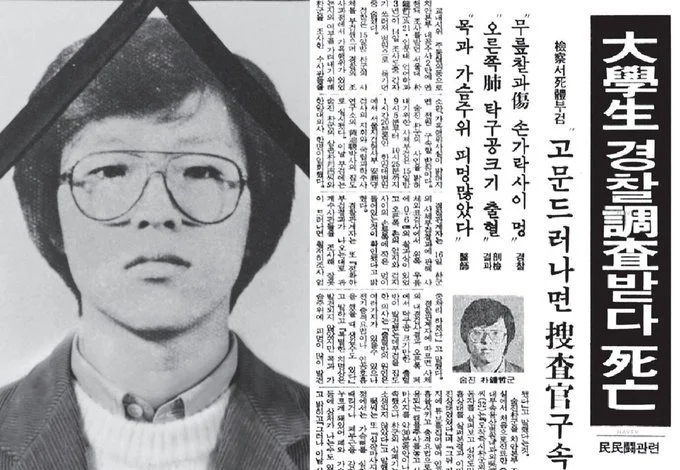

Take Park Jong-chul, 1987: a 21-year-old student activist, dragged to police HQ for "harboring a fugitive." Prosecutors green-lit the interrogation. Twenty hours of sleep denial, then waterboarding: rags over his face, poured till he drowned on dry land. Electric prods followed, but he wouldn't confess names. By morning, he was dead. "Shock," they lied, but Park’s autopsy exposed the truth: torture logs, and police signatures.

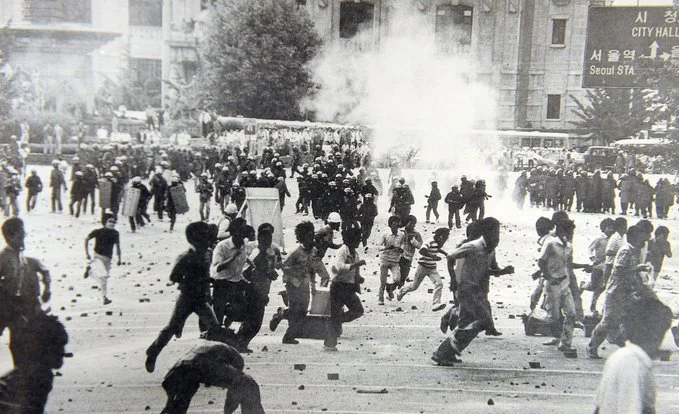

This sparked the June Uprising that cracked Chun’s regime. But the prosecutors? Untouched. This was the system’s rhythm: confessions as currency, bodies as collateral—casting stones without reckoning their own shortcomings.

We kept the chains, just swapped masters. From Rhee to Chun, the "Republic of Prosecutors" thrived: unaccountable, unchecked, extracting "justice" drop by bloody drop.

IV. The Democratic Paradox: Reform Without Revolution

Before 1987, South Korea was not a democracy. It was a military-controlled state, transitioning between authoritarian regimes that held elections but suppressed political opposition. The KCIA, police, and prosecutors worked in tandem to surveil, harass, and imprison critics.

That year marked a turning point: mass demonstrations in June forced constitutional reforms and direct presidential elections. A new democratic chapter began, but the institutions of the authoritarian state, especially the prosecution service, were left largely intact.

1987, Seoul - Korea. Students protests under fire from police with tear gas. (Korean Herald)

After democratization, expectations rose that the prosecution would be reformed. Yet even liberal administrations struggled to break its power.

“Presidents who tried often found themselves targeted later by the very prosecutors they failed to disarm.”

Special prosecutor laws were introduced, jury trials experimented with, and investigatory powers trimmed, but the core structure has remained. Every reform has circled the same untouched core: a single, vertical chain of command that answers to itself.

Prosecutors still supervise the police. They still hold exclusive indictment authority. And they still operate within a single national hierarchy controlled by the Ministry of Justice.

Why is this system so hard to change?

V. Comparison: Korea vs. the American Prosecutorial Model

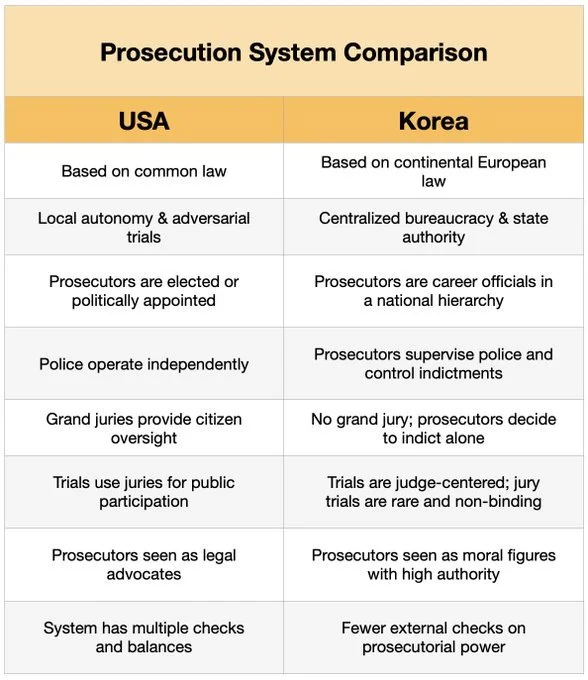

Understanding Korea’s unique prosecution system becomes clearer when compared with the American approach.

Comparison chart. A quick look at the fundamental differences between American and Korean prosecutorial systems.

Legal Tradition: South Korea’s system is rooted in the continental European tradition, emphasizing centralized bureaucracy, state authority, and career civil service. In contrast, the American legal system is based on Anglo-American common law, built around adversarial trials, local autonomy, and popular accountability.

Structure and Power: Korean prosecutors are part of a single national hierarchy under the Ministry of Justice. They possess investigative powers, can supervise the police, and have exclusive authority to indict. In the U.S., prosecutors are often elected (district attorneys) or politically appointed (U.S. attorneys), with police departments operating independently and investigations often conducted without prosecutorial oversight.

Checks and Balances: The U.S. uses grand juries in serious cases, which adds a layer of citizen oversight before charges are filed. Korea has no grand jury system, and prosecutors decide independently whether to indict. This gives Korean prosecutors greater discretionary power—but with fewer external checks.

Courtroom Dynamics: American criminal trials are jury-based, emphasizing public participation. Korea only introduced limited jury trials in 2008, and even then, the jury's decision is not binding. Korean trials remain judge-centered, reinforcing bureaucratic control over criminal justice.

Culture and Perception: In the U.S., prosecutors are seen as advocates in an adversarial system—balanced by defense attorneys and judges. In Korea, prosecutors have long been seen as moral arbiters, quasi-judicial figures with institutional prestige. This cultural authority has historically shielded them from scrutiny.

Together, these contrasts explain why Korea’s justice still feels like inquisition, and why dismantling it is both revolutionary and perilous.

VI. Germany and Japan Moved On. Why Didn’t Korea?

The prosecution model Korea inherited was based on systems developed in 19th-century Germany and Meiji-era Japan. But both of those countries—unlike Korea—reformed their legal systems significantly after authoritarian rule.

In Germany, prosecutors remain powerful civil servants, but their authority is restrained by rigorous court oversight and constitutional protections for defendants. The Nazi-era abuses prompted Germany to build strong judicial independence and decentralization into its postwar justice system. Modern German prosecutors do not dominate police or trials; their role is legally bounded and subject to institutional checks.

In Japan, the legacy of central prosecutorial authority remains—but even there, reforms have softened its impact. Japan introduced the "saiban-in" system in 2009, which allows lay judges to participate in criminal trials alongside professionals. Public scrutiny and judicial culture have pushed Japan to handle high-profile prosecutions with extreme caution. Moreover, Japanese prosecutors tend to be far more selective, often declining to prosecute cases unless the evidence is nearly ironclad—thus avoiding overreach.

High Court - Seoul.

In contrast, South Korea retained the most coercive and hierarchical features of the model it received: direct police supervision, unified national hierarchy, and political susceptibility. Even after democratization, Korea continued to expand prosecutorial reach instead of curbing it. While Germany and Japan evolved, Korea remained institutionally frozen—a modern democracy operating with an imperial-era enforcement logic.

“Korea modernized everything but its inquisition.”

This historical lag helps explain why Korean prosecutors became such dominant political actors, and why reform has been so contentious. Other nations that inspired Korea's legal origins moved forward. Korea, until recently, did not.

VII. The Confucian Legacy: Order Over Accountability

To understand why Korea’s prosecution system persisted for so long, and why it commanded such institutional loyalty, it is essential to consider the role of Confucian culture. Rooted in centuries of Korean tradition, Confucianism emphasizes hierarchy, duty, moral rectitude, and reverence for authority. These values deeply shaped Korea’s bureaucratic and legal institutions, including the prosecutorial corps.

In practice, this meant that prosecutors were not merely seen as legal technicians. They were viewed as moral officials—arbiters of right and wrong with quasi-judicial prestige. The structure of the Prosecution Service mirrored Confucian ideals: centralized, orderly, and bound by a strict seniority system. Promotions and deference were based less on innovation or independence than on examination scores, rank, and obedience to superiors.

This cultural context had strengths. It fostered national unity, institutional discipline, and an elite civil service that valued meritocratic entry. In moments of political chaos, the prosecution posed as a force of continuity and moral order. But the weaknesses were profound.

Confucian hierarchy discouraged dissent and protected incumbents. Prosecutors were expected to conform, not question. Internal accountability was preferred over public transparency. When misconduct occurred, it was often buried to preserve institutional dignity. And when political leaders weaponized the system, few inside had the autonomy—or courage—to resist.

“Even a moral bureaucracy can enforce injustice if its structure and culture resist external scrutiny.”

Moreover, this culture enabled the illusion of neutrality. Because prosecutors were viewed as upright civil servants rather than partisan actors, their actions were often accepted without challenge. But as history shows, even a moral bureaucracy can enforce injustice if its structure and culture resist external scrutiny.

The fusion of colonial authority with Confucian hierarchy created a uniquely rigid prosecutorial system: powerful, disciplined, and slow to reform. Until recently, that structure was less a legacy of democracy than a continuation of inherited obedience. The system’s loyalty was to order, not justice; obedience, not truth.

Another cultural wrinkle lies in age and hierarchy. In Korea, judges often enter the bench directly after completing legal training, making them comparatively young — sometimes in their late twenties or early thirties. Prosecutors, by contrast, rise through senior bureaucratic ranks, often decades older and institutionally entrenched. This imbalance subtly tilts courtroom dynamics: younger judges, socialized to defer to seniority, may hesitate to overrule veteran prosecutors. In this way, Confucian respect for age and rank continues to shape modern adjudication as much as legal code.

VIII. The 2025 Reckoning: Reform or Political Theater?

In June 2025, the newly elected government of Lee Jae-myung pushed a historic bill through the National Assembly: a plan to abolish the Prosecution Service entirely. Passed in September, the law dissolves the 78-year-old institution and transfers its powers to two new agencies: one for investigation, another for indictment.

Supporters hailed it as a long-overdue reckoning. Opponents, mostly conservatives, decried it as unconstitutional and dangerous. Both sides agreed: nothing this drastic had ever been done in Korea's legal history.

High Court - Seoul.

Yet this moment demands deeper questions. Is this truly reform, an effort to build a more democratic and accountable legal system? Or is it also, at least in part, a political act of erasure and consolidation?

For the political left, abolishing the Prosecution Service has long been symbolic. It is the institutional scapegoat for decades of selective justice and conservative overreach. But critics argue that the reforms may serve another purpose: shielding current leaders from the same prosecutorial scrutiny they once condemned. Reform and revenge are not always so easily distinguished.

“The spectacle of justice—the morning raids, the televised perp walks, the ritual humiliation of powerful figures—has become part of the public theater.”

For the right, the prosecution is more than just an institution—it is an anchor. Conservatives see it as a critical check on political corruption and a necessary engine for enforcing moral norms. Many fear that its dismantling will leave a vacuum where no agency is strong or neutral enough to investigate power. Their loyalty is partly ideological, but also cultural. The prosecution has become a vessel of trust when other institutions—parliament, police, media—have failed.

And what about the public? Polls show that Koreans are conflicted. Many resent the prosecution’s politicization, but also crave the catharsis of high-profile trials. This ritual of punishment has become the nation’s moral theater, where power is purified through humiliation. This is not just legal accountability. It is cultural cleansing.

The inquisition, in that sense, may be less about justice than about ritual: a way to reaffirm social order by punishing those who deviate from the righteous path. Reforming that impulse is harder than rewriting law. It requires a cultural reckoning Korea has only just begun.

IX. Weighing the Pros and Cons: Justice or Jeopardy?

Pros:

Ends a long legacy of politicized investigations.

Separates powers, introducing checks and balances.

Opens the door to more democratic, transparent oversight.

Cons:

Risk of weakening Korea's capacity to investigate elite corruption.

Implementation could be chaotic and inconsistent.

The new agencies may inherit the same bad habits.

Provocative questions remain: If this system was born in empire and grew under dictatorship, why did democracy take so long to dismantle it? Is Korea finally closing the book on colonial legalism—or just rewriting it under new titles?

Conclusion: An Inquisition Deferred

It is time to heal. I have felt the scar on Korea’s scales of justice—etched now in halls of worship and in the hearts of believers who seem to threaten the administration’s will.

The prosecution was never just a legal body. I have come to know it as a symbol of power, fear, and continuity. Its abolition is a bold experiment in rebirth—but whether it brings renewal or decay depends on what we do next.

“Is the inquisition over—or has it simply moved into new chambers, with new tools but the same old logic?”

In a country where memory and tradition run deep but reform crawls slowly, the past is never really past. Is the inquisition over, or just rebranded? Either way, history is watching.

Sources and Suggested Readings

James Constant, “South Korea Is Spiraling Toward a Polarized Justice System,” The Diplomat, May 2024.

Neil Chisholm, “Prosecutorial Independence in Comparative Perspective,” Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 2025.

Korean Ministry of Justice, Public Prosecutor’s Office Act (1949).

J.-I. Yoo, “Legal Education and Judicial System in the ROK,” UNAFEI Report, 1990.

Hankyoreh Editorial Board, “78년만에 폐지되는 검찰, 후속 개혁안 촘촘하게,” September 2025.

Korea Times, “Prosecutors in the US and Korea,” June 2011.

Chosun Ilbo, Opinion Section, “Is Dismantling the Prosecutors' Office Unconstitutional?” September 2025.

Bitter Winter, Massimo Introvigne, “Free Mother Han! Free Pastor Son!” October 2025.

Forum for Religious Freedom Europe (FOREF), Jan Figel, “South Korea’s Religious Purge,” September 2025.

Realmeter Survey, “Public Opinion on Prosecution Reform,” June 2025.

ACLED South Korea Political Demonstration Tracker, January–October 2025.

Cambridge University Press, Law and Custom in Korea: Colonial Law and the Legal System 1910–1945.

Human Rights Watch, Reports on Torture in South Korea, 1970s–1980s (archived).

United Nations Human Rights Committee, Observations on the Republic of Korea, ICCPR Article 9 and 14 reviews, various years.

Student Park Jong-chul. Died, 1987 at the hands of prosecutors.

Take Park Jong-chul, 1987: a 21-year-old student activist, dragged to police HQ for "harboring a fugitive." Prosecutors green-lit the interrogation. Twenty hours of sleep denial, then waterboarding: rags over his face, poured till he drowned on dry land. Electric prods followed, but he wouldn't confess names. By morning, he was dead. "Shock," they lied, but Park’s autopsy exposed the truth: torture logs, and police signatures.

This sparked the June Uprising that cracked Chun’s regime. But the prosecutors? Untouched. This was the system’s rhythm: confessions as currency, bodies as collateral—casting stones without reckoning their own shortcomings.

We kept the chains, just swapped masters. From Rhee to Chun, the "Republic of Prosecutors" thrived: unaccountable, unchecked, extracting "justice" drop by bloody drop.

IV. The Democratic Paradox: Reform Without Revolution

Before 1987, South Korea was not a democracy. It was a military-controlled state, transitioning between authoritarian regimes that held elections but suppressed political opposition. The KCIA, police, and prosecutors worked in tandem to surveil, harass, and imprison critics.

That year marked a turning point: mass demonstrations in June forced constitutional reforms and direct presidential elections. A new democratic chapter began, but the institutions of the authoritarian state, especially the prosecution service, were left largely intact.

1987, Seoul - Korea. Students protests under fire from police with tear gas. (Korean Herald)

After democratization, expectations rose that the prosecution would be reformed. Yet even liberal administrations struggled to break its power.

“Presidents who tried often found themselves targeted later by the very prosecutors they failed to disarm.”

Special prosecutor laws were introduced, jury trials experimented with, and investigatory powers trimmed, but the core structure has remained. Every reform has circled the same untouched core: a single, vertical chain of command that answers to itself.

Prosecutors still supervise the police. They still hold exclusive indictment authority. And they still operate within a single national hierarchy controlled by the Ministry of Justice.

Why is this system so hard to change?

V. Comparison: Korea vs. the American Prosecutorial Model

Understanding Korea’s unique prosecution system becomes clearer when compared with the American approach.

Comparison chart. A quick look at the fundamental differences between American and Korean prosecutorial systems.

Legal Tradition: South Korea’s system is rooted in the continental European tradition, emphasizing centralized bureaucracy, state authority, and career civil service. In contrast, the American legal system is based on Anglo-American common law, built around adversarial trials, local autonomy, and popular accountability.

Structure and Power: Korean prosecutors are part of a single national hierarchy under the Ministry of Justice. They possess investigative powers, can supervise the police, and have exclusive authority to indict. In the U.S., prosecutors are often elected (district attorneys) or politically appointed (U.S. attorneys), with police departments operating independently and investigations often conducted without prosecutorial oversight.

Checks and Balances: The U.S. uses grand juries in serious cases, which adds a layer of citizen oversight before charges are filed. Korea has no grand jury system, and prosecutors decide independently whether to indict. This gives Korean prosecutors greater discretionary power—but with fewer external checks.

Courtroom Dynamics: American criminal trials are jury-based, emphasizing public participation. Korea only introduced limited jury trials in 2008, and even then, the jury's decision is not binding. Korean trials remain judge-centered, reinforcing bureaucratic control over criminal justice.

Culture and Perception: In the U.S., prosecutors are seen as advocates in an adversarial system—balanced by defense attorneys and judges. In Korea, prosecutors have long been seen as moral arbiters, quasi-judicial figures with institutional prestige. This cultural authority has historically shielded them from scrutiny.

Together, these contrasts explain why Korea’s justice still feels like inquisition, and why dismantling it is both revolutionary and perilous.

VI. Germany and Japan Moved On. Why Didn’t Korea?

The prosecution model Korea inherited was based on systems developed in 19th-century Germany and Meiji-era Japan. But both of those countries—unlike Korea—reformed their legal systems significantly after authoritarian rule.

In Germany, prosecutors remain powerful civil servants, but their authority is restrained by rigorous court oversight and constitutional protections for defendants. The Nazi-era abuses prompted Germany to build strong judicial independence and decentralization into its postwar justice system. Modern German prosecutors do not dominate police or trials; their role is legally bounded and subject to institutional checks.

In Japan, the legacy of central prosecutorial authority remains—but even there, reforms have softened its impact. Japan introduced the "saiban-in" system in 2009, which allows lay judges to participate in criminal trials alongside professionals. Public scrutiny and judicial culture have pushed Japan to handle high-profile prosecutions with extreme caution. Moreover, Japanese prosecutors tend to be far more selective, often declining to prosecute cases unless the evidence is nearly ironclad—thus avoiding overreach.

High Court - Seoul.

In contrast, South Korea retained the most coercive and hierarchical features of the model it received: direct police supervision, unified national hierarchy, and political susceptibility. Even after democratization, Korea continued to expand prosecutorial reach instead of curbing it. While Germany and Japan evolved, Korea remained institutionally frozen—a modern democracy operating with an imperial-era enforcement logic.

“Korea modernized everything but its inquisition.”

This historical lag helps explain why Korean prosecutors became such dominant political actors, and why reform has been so contentious. Other nations that inspired Korea's legal origins moved forward. Korea, until recently, did not.

VII. The Confucian Legacy: Order Over Accountability

To understand why Korea’s prosecution system persisted for so long, and why it commanded such institutional loyalty, it is essential to consider the role of Confucian culture. Rooted in centuries of Korean tradition, Confucianism emphasizes hierarchy, duty, moral rectitude, and reverence for authority. These values deeply shaped Korea’s bureaucratic and legal institutions, including the prosecutorial corps.

In practice, this meant that prosecutors were not merely seen as legal technicians. They were viewed as moral officials—arbiters of right and wrong with quasi-judicial prestige. The structure of the Prosecution Service mirrored Confucian ideals: centralized, orderly, and bound by a strict seniority system. Promotions and deference were based less on innovation or independence than on examination scores, rank, and obedience to superiors.

This cultural context had strengths. It fostered national unity, institutional discipline, and an elite civil service that valued meritocratic entry. In moments of political chaos, the prosecution posed as a force of continuity and moral order. But the weaknesses were profound.

Confucian hierarchy discouraged dissent and protected incumbents. Prosecutors were expected to conform, not question. Internal accountability was preferred over public transparency. When misconduct occurred, it was often buried to preserve institutional dignity. And when political leaders weaponized the system, few inside had the autonomy—or courage—to resist.

“Even a moral bureaucracy can enforce injustice if its structure and culture resist external scrutiny.”

Moreover, this culture enabled the illusion of neutrality. Because prosecutors were viewed as upright civil servants rather than partisan actors, their actions were often accepted without challenge. But as history shows, even a moral bureaucracy can enforce injustice if its structure and culture resist external scrutiny.

The fusion of colonial authority with Confucian hierarchy created a uniquely rigid prosecutorial system: powerful, disciplined, and slow to reform. Until recently, that structure was less a legacy of democracy than a continuation of inherited obedience. The system’s loyalty was to order, not justice; obedience, not truth.

Another cultural wrinkle lies in age and hierarchy. In Korea, judges often enter the bench directly after completing legal training, making them comparatively young — sometimes in their late twenties or early thirties. Prosecutors, by contrast, rise through senior bureaucratic ranks, often decades older and institutionally entrenched. This imbalance subtly tilts courtroom dynamics: younger judges, socialized to defer to seniority, may hesitate to overrule veteran prosecutors. In this way, Confucian respect for age and rank continues to shape modern adjudication as much as legal code.

VIII. The 2025 Reckoning: Reform or Political Theater?

In June 2025, the newly elected government of Lee Jae-myung pushed a historic bill through the National Assembly: a plan to abolish the Prosecution Service entirely. Passed in September, the law dissolves the 78-year-old institution and transfers its powers to two new agencies: one for investigation, another for indictment.

Supporters hailed it as a long-overdue reckoning. Opponents, mostly conservatives, decried it as unconstitutional and dangerous. Both sides agreed: nothing this drastic had ever been done in Korea's legal history.

High Court - Seoul.

Yet this moment demands deeper questions. Is this truly reform, an effort to build a more democratic and accountable legal system? Or is it also, at least in part, a political act of erasure and consolidation?

For the political left, abolishing the Prosecution Service has long been symbolic. It is the institutional scapegoat for decades of selective justice and conservative overreach. But critics argue that the reforms may serve another purpose: shielding current leaders from the same prosecutorial scrutiny they once condemned. Reform and revenge are not always so easily distinguished.

“The spectacle of justice—the morning raids, the televised perp walks, the ritual humiliation of powerful figures—has become part of the public theater.”

For the right, the prosecution is more than just an institution—it is an anchor. Conservatives see it as a critical check on political corruption and a necessary engine for enforcing moral norms. Many fear that its dismantling will leave a vacuum where no agency is strong or neutral enough to investigate power. Their loyalty is partly ideological, but also cultural. The prosecution has become a vessel of trust when other institutions—parliament, police, media—have failed.

And what about the public? Polls show that Koreans are conflicted. Many resent the prosecution’s politicization, but also crave the catharsis of high-profile trials. This ritual of punishment has become the nation’s moral theater, where power is purified through humiliation. This is not just legal accountability. It is cultural cleansing.

The inquisition, in that sense, may be less about justice than about ritual: a way to reaffirm social order by punishing those who deviate from the righteous path. Reforming that impulse is harder than rewriting law. It requires a cultural reckoning Korea has only just begun.

IX. Weighing the Pros and Cons: Justice or Jeopardy?

Pros:

Ends a long legacy of politicized investigations.

Separates powers, introducing checks and balances.

Opens the door to more democratic, transparent oversight.

Cons:

Risk of weakening Korea's capacity to investigate elite corruption.

Implementation could be chaotic and inconsistent.

The new agencies may inherit the same bad habits.

Provocative questions remain: If this system was born in empire and grew under dictatorship, why did democracy take so long to dismantle it? Is Korea finally closing the book on colonial legalism—or just rewriting it under new titles?

Conclusion: An Inquisition Deferred

It is time to heal. I have felt the scar on Korea’s scales of justice—etched now in halls of worship and in the hearts of believers who seem to threaten the administration’s will.

The prosecution was never just a legal body. I have come to know it as a symbol of power, fear, and continuity. Its abolition is a bold experiment in rebirth—but whether it brings renewal or decay depends on what we do next.

“Is the inquisition over—or has it simply moved into new chambers, with new tools but the same old logic?”

In a country where memory and tradition run deep but reform crawls slowly, the past is never really past. Is the inquisition over, or just rebranded? Either way, history is watching.

Sources and Suggested Readings

James Constant, “South Korea Is Spiraling Toward a Polarized Justice System,” The Diplomat, May 2024.

Neil Chisholm, “Prosecutorial Independence in Comparative Perspective,” Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 2025.

Korean Ministry of Justice, Public Prosecutor’s Office Act (1949).

J.-I. Yoo, “Legal Education and Judicial System in the ROK,” UNAFEI Report, 1990.

Hankyoreh Editorial Board, “78년만에 폐지되는 검찰, 후속 개혁안 촘촘하게,” September 2025.

Korea Times, “Prosecutors in the US and Korea,” June 2011.

Chosun Ilbo, Opinion Section, “Is Dismantling the Prosecutors' Office Unconstitutional?” September 2025.

Bitter Winter, Massimo Introvigne, “Free Mother Han! Free Pastor Son!” October 2025.

Forum for Religious Freedom Europe (FOREF), Jan Figel, “South Korea’s Religious Purge,” September 2025.

Realmeter Survey, “Public Opinion on Prosecution Reform,” June 2025.

ACLED South Korea Political Demonstration Tracker, January–October 2025.

Cambridge University Press, Law and Custom in Korea: Colonial Law and the Legal System 1910–1945.

Human Rights Watch, Reports on Torture in South Korea, 1970s–1980s (archived).

United Nations Human Rights Committee, Observations on the Republic of Korea, ICCPR Article 9 and 14 reviews, various years.