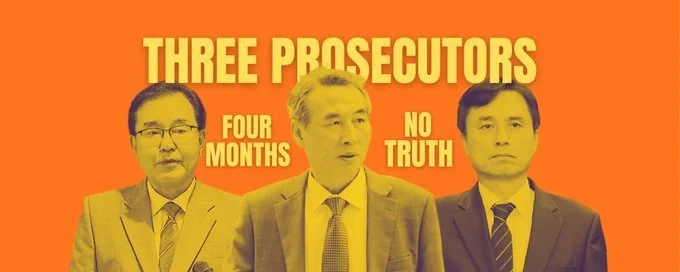

Three Prosecutors. Four Months. No Truth.

Inside South Korea’s Special Counsel Crisis and the Legacy It Revealed.

by Rev. Demian Dunkley

It began, as so many scandals in South Korea do, with promises of purification. Three special prosecutors were appointed this summer to cleanse the nation of its latest sins: treason, corruption, and cover-up. Four months later, all three are mired in confusion. Not one has proved its central claim. What began as a pledge to restore public faith in justice has devolved into spectacle, raids without convictions, headlines without evidence, and prosecutors chasing the ghosts of their own ambitions.

The investigations, into alleged “insurrection” by former president Yoon Suk-yeol, supposed corruption by his wife Kim Keon-hee, and the death of a young Marine, were meant to be independent, decisive, and surgical. Instead, they have become symbols of drift. Even the Chosun Ilbo, often sympathetic to the government, lamented that investigators were “clinging to side matters rather than clarifying the core.”

By November, it was no longer clear who was on trial, the defendants or the system itself. Now, as their mandates expire, the spectacle is collapsing under its own contradictions. The “Kim Keon-hee probe,” which began as a stock-manipulation case, has produced only minor indictments. The “insurrection inquiry,” designed to expose a grand act of treason, has shrunk to procedural quibbles. And the “Marine death” team, once pursuing truth about a soldier’s drowning, is now interrogating other investigators. Together they form a trilogy of futility, each born in moral fury and ending in bureaucratic absurdity. Lie-detector tests on witnesses. Prosecutors investigating prosecutors. A lead special counsel accused of insider trading. The theater of justice has become indistinguishable from parody.

The Kim Keon-hee Probe — When the Prosecutor Becomes the Story

The case against the former First Lady was supposed to showcase the independence of Korea’s legal system. It has done the opposite.

After months of raids and interrogations, the investigation has yielded little beyond spectacle: Chanel handbags, a Graff necklace, and a collapsing moral center. In October, Special Counsel Min Joong-ki’s team seized luxury items allegedly given to Kim by a Unification Church associate. The counsel trumpeted the discovery, yet the same month, forty prosecutors assigned to Min’s task force staged an unprecedented rebellion, demanding to be sent back to their home offices. JoongAng Daily described the protest as “mutiny inside the special counsel.”

Then came tragedy. A local official in Yangpyeong County, questioned by Min’s investigators about a real-estate case linked to Kim, took his own life. He left behind 21 pages accusing prosecutors of coercion and even forgery of interrogation records. His lawyer has filed a lawsuit against the special counsel for abuse of power and document fabrication. Opposition lawmakers called it “a witch hunt that killed an innocent man.”

And still the case lurches on, now led by a prosecutor whose own record mirrors the charges he is bringing. In mid-October, Chosun Ilbo revealed that Min Joong-ki himself once traded shares in Neo Semitech, the very company at the center of Kim Keon-hee’s stock-manipulation scandal. While thousands of investors were wiped out, Min sold his holdings just before the stock was suspended, pocketing roughly ₩100 million.

Ruling-party lawmakers call it hypocrisy; conservative editorials have demanded his resignation. Min insists he simply “followed a broker’s advice,” refusing to name the broker or explain the timing. JoongAng Daily warned that unless he provides full transparency, “the credibility of his entire investigation is at risk.”

A prosecutor who profited like an insider now investigates another for the same. A team meant to uncover corruption is consumed by it. By November, the Kim Keon-hee probe had become less about justice than about survival.

The Insurrection Inquiry — A Coup on Trial

If the Kim case is imploding, the Yoon Suk-yeol insurrection trial is the country’s grandest spectacle, equal parts courtroom drama and political exorcism.

The special counsel led by Cho Eun-seok is probing Yoon’s declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024, a six-hour decree that triggered his impeachment and removal. Yoon now sits in a detention cell, tried for insurrection and abuse of power. His trial, televised by special permission, is being called Korea’s most dramatic political reckoning in decades.

The proceedings have produced moments that border on the surreal. A retired major general testified that Yoon ordered him to detain opposition lawmakers so he could “shoot and kill them all himself.” Former aides describe a president consumed by paranoia, convinced “anti-state forces” were conspiring against him.

To supporters, this is overreach, a vendetta disguised as virtue. The opposition People Power Party argues that the investigation was pre-ordained, that Yoon’s arrest after just weeks of inquiry proves the special counsel had its verdict before the trial. To others, it is long-delayed accountability for a leader who flirted with authoritarian rule.

The line between justice and revenge has blurred. When the court approved live broadcast of the hearings, legal scholars called it “transparency,” while critics called it “theater.” In either case, the prosecution of a former president, once unthinkable, has become a public ritual, part penance, part entertainment.

The Marine Death Case — The Tragedy That Turned Political

The third investigation, led by Special Counsel Lee Myeong-hyeon, began with a drowning.

In July 2023, Marine Corporal Chae Su-geun was swept away by floodwaters while searching for missing civilians. He wore no life vest. When military investigators traced responsibility to senior officers, the Defense Ministry suddenly intervened, recalling reports, stalling referrals, and allegedly shielding commanders.

By mid-2025, whistleblowers claimed a Blue House-ordered cover-up, and Parliament appointed an independent counsel. In October, Lee sought arrest warrants for five high-ranking officials, including former Defense Minister Lee Jong-sup, accusing them of abuse of power and evidence tampering. Investigators say the minister stopped the case “after President Yoon flew into a rage” that one of his generals was being blamed.

Even now, Yoon cannot escape the dragnet. On October 23, the special counsel summoned the former president for questioning as a criminal suspect in the cover-up. Yoon refused to appear voluntarily. He may be compelled to testify under guard, an extraordinary humiliation for a former commander-in-chief.

Families of the dead Marine demand justice; conservatives decry political vengeance. Whichever side prevails, the tragedy of one young soldier has become another battleground in Korea’s endless legal war.

The Pattern — Law Without Truth

Across all three probes, the pattern is unmistakable: investigative drift, political theater, and moral exhaustion.

The special-prosecutor system was created in the 1990s to curb prosecutorial overreach by empowering “independent” teams. Today those teams look less independent than unaccountable, vast bureaucracies pursuing headlines instead of justice.

In the Kim Keon-hee case, prosecutors leak luxury brands instead of evidence. In the insurrection trial, they televise testimony like a courtroom serial. In the Marine inquiry, they summon an impeached president more for symbolism than necessity. Each investigation extends indefinitely, expanding its scope the moment facts fail to fit. The result is not truth but momentum, the appearance of motion that conceals the absence of conclusion.

This is not new. Korea’s prosecution service was born under Japanese colonial rule, perfected under military dictatorship, and only partially reformed in democracy. Its prosecutors were trained not as neutral arbiters but as guardians of state order, a tradition of moral absolutism masquerading as law. Even after democratization, that DNA persisted: the prosecutor as inquisitor, the suspect as sinner, confession as proof.

Three decades of reform have trimmed its powers but not its instincts. What was once called the Republic of Prosecutorsendures. Public confidence tells the story. Trust in the judiciary hovers around 26 percent, among the lowest in the OECD. Each scandal widens the gap between legality and legitimacy.

The Human Cost

But the damage goes deeper than politics. It reaches into the conscience of a nation.

A local official who could not endure another interrogation. An 82-year-old religious leader, Dr. Hak Ja Han, held in a solitary cell by the same prosecutorial establishment that raids churches in the name of justice. A drowned Marine whose death became political collateral.

Each case exposes a justice system that punishes to prove its virtue, a system more concerned with performance than proportion.

Since August, more than 120 raids and interrogations have been conducted by special counsels nationwide, most without convictions. Koreans have seen this movie before. Every generation is promised a new beginning; every act ends in the same courtroom. Public fatigue has turned to quiet disbelief. The show goes on, but the audience no longer claps.

The Mirror Held to the State

Four months into the great cleansing, Korea’s special counsels have indicted nearly everyone but themselves. They promised to expose corruption and ended up exposing the system.

In the Republic of Prosecutors, justice has become performance, a ritual of accusation that never reaches atonement. The law now performs righteousness even as faith in it collapses. The robes remain, the stage lights still burn, but the actors no longer notice that the audience has stopped believing.

Sources and References

Chosun Ilbo, Oct. 29, 2025 — “Special Prosecutor Probes Prosecution’s Lenient Handling of Kim Keon-hee Case.”

JoongAng Daily, Nov. 4, 2025 — “Ex-First Lady Kim Keon Hee Files for Bail Amid Bribery Trial.”

JoongAng Daily, Oct. 22, 2025 — “Special Probe Team Receives Luxury Items Allegedly Given to Ex-First Lady.”

JoongAng Daily, Oct. 14, 2025 — “Lawyer of Late Yangpyeong County Official Vows to Sue Special Counsel Team.”

JoongAng Daily, Oct. 19, 2025 — “Special Counsel Investigating Ex-First Lady Faces Own Capital Gains Probe.”

South China Morning Post, Nov. 4, 2025 — “Yoon Planned to Capture, Kill Political Rivals: Court.”

Korea JoongAng Daily, Nov. 3, 2025 — “Special Counsel Seeks Arrest Warrant for PPP Lawmaker Over Martial Law Role.”

Yonhap News / KBS World, Oct. 13, 2025 — “Yoon to Be Summoned for Questioning Next Week in Marine Death Case.”

Korea Times, Oct. 20, 2025 — “Special Counsel Seeks Arrest Warrant for Ex-Defense Chief and 4 Others in Marine Death Probe.”